On Digital Subjectivity

All politics begin with a relation between a subject and social reality. A subject is born into an interacting world of states, violence, and other people. She may believe taxes are too high or the military budget should be lowered, but these are normative descriptions imposed upon the current, external political situation. This relationship is meditated by language, and language is mediated by the symbolic order. All political pronouncements, at their core, invariably account for otherness. Even Trump can’t control all political otherness; The most powerful political agent in the United States believes he’s the most opposed. Trump’s political project, with desiring subjects attempting to overcome the barriers to their pure enjoyment, is evidence of language’s political importance.

In some ways, social media democratizes the relationship between politics and communication. The decline of typical corporate media ostensibly opens spaces for new voices – indeed, the number of reasonably significant voices has increased. But this view of democratic politics is naïve; The number of voices or voiced opinions is necessary, but insufficient, for a proper democracy. Democracy, as I have argued previously, is an autoimmune relation between communicating subjects. The opportunity to communicate one’s desire on TikTok doesn’t functionally alter the subject’s relationship with social reality. Communication is more explicit, but the psychoanalytical fundamentals of the relationship remain the same.

Social media is an acceleration of language; The contradictions of social media’s symbolic environment apply equally to language itself. All communication involves symbolism. When someone says “I love you” to their partner, not everything is encapsulated within the statement – a highly complex system of desire mediates and restricts the speaker’s communication. “I love you” is an inscription within language, a deference of affect through language. Social media is unique in its immediacy and opaqueness. Digital subjectivity interpolates the subject as a node in a wider, more significant network of exchange. Posting “I love my girlfriend” on an Instagram story is clearly different from telling her “I love you,” since the conscious audience (girlfriend à followers + girlfriend, receiving reaffirmation of commitment), signifier (directed at situated partner à unintimate, performative utterance), and signified (love à to be seen loving) change. This distinction is the theoretical basis for social media’s implication on political communication.

The fundamental issue with the politics of social media is the problem of visibility and desire – the mechanisms through which political discourse is rendered legible, amplified, and made to matter “digital surveillance” fails to address the relational reconfiguration of the subject’s relation to politics itself. The point is not merely that corporations aggregate and exploit our data, but that the very structure of social media reshapes how democracy is perceived, enacted, and experienced at the level of subjectivity.

The communicative problem naturally follows its epistemic environment. Today, capitalist realism, the universal dissemination of language towards consumption, constrains political subjectivity. The fundamental tendency of capitalism realism is disavowal – “I know consulting is useless, but I want to be a consultant; I’m meaningfully different than other consultants because I know consulting is useless.” Disavowal is central to the sense of political “agency” afforded to the subject by capitalist ideology, since disavowal implies a distanced relationship between object (which one knows is worthless) and subject (who is then free to fetishize the worthlessness of the object). Disavowal then informs the automatization of ‘individual democracy’ – one can feel as though they’re “doing politics” while doing nothing at all. The idea that “everything is political” is, in its broadest sense, true – identity, consumption, production, communication are all constrained by politics. But the atomization of politics informs a politics of consumption; One “does politics” by consuming or producing media. This consumption of symbolic narratives does politics for us.

The political terrain of social media is infinitely plastic and self-replicating. Subjects, even those who consciously disavow of capitalism or capitalist realism, have stakes in its continuation. In fantasy, a subject believes it desires the object of desire – whether it be political change or a new iPhone. However, to sustain fantasy, the object of desire is essential, so the subject actually enjoys overcoming the barrier to her enjoyment. This is why it’s easier to imagine a Brown’s fan (who’s team has been historically dreadful) happier than a Chiefs or Patriots fan after winning a Super Bowl – the barriers to enjoyment were more arduous. Similarly, social media outrage can never be placated, because the purpose is to be outraged, not to resolve the contents of outrage itself. Every atomized, digital, and political subject is enmeshed within the personal confines of their fantasy – whether the barrier is immigrants, Trump, or the rich is wholly significant, since each fantasy is structured similarly. When posting, there is no clear subject that’s being communicated to – the audience and algorithm are an inconceivable totality. The communicative act of posting, then, is perhaps the clearest example of communication with the big Other, or the virtual figure presupposed by language. The symbolic, political significance imparted upon the individual posting means social media is an optimal terrain from which to carry fantasy onto otherness.

The essence of digital communicative capitalism is exemplified by automation. On X, it’s common to see a botted (or highly prolific slop-producing) account post something related to the day’s news. The obvious goal of these accounts is to earn advertising revenue, so the posts will always replicate the ideology of the target demographic. In response, another botted (or highly prolific slop-producing) “reply guy” will intervene, arguing in the replies while replicating the ideology of its target demographic. The creation of ideologically perfect AIs to argue against each other straightforwardly point to digital capitalism’s interpassive quality: Let the machines do the politics, and you can enjoy. As Fisher argued:

“Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombiemaker; but the living flesh it converts into dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us.” [1]

Social media’s matrix of desire features a certain dissonance: Brainrot. Brainrot is a fracturing of subjectivity, the reduction of communication to merely signified blips. Language and symbolism lose referent to time and place – only phenomenon matter. Our endemic conceptualization of brainrot is self-referential: We’re all addicted to digital patterns of consumption and sublimation, we know it’s for the worse, and all we can do is deprecate our addictions. The irony here is that problematizing brainrot is a sublimated, brainrotted process. This paradox enables a brainrot of disavowal: A brainrot that understands its absurd impulses and maximizes them. “Accelerationist brainrot” TikToks, where the humor lies in maximizing absurdity and meaninglessness, are symptomatic of brainrot’s symbolic contradictions.

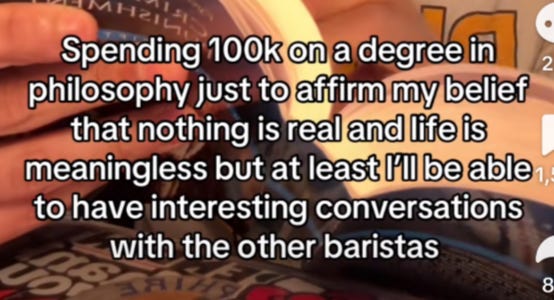

With TikTok, symbolic significance relies upon abstraction. Take, for example, the following post:

The act of studying philosophy is incorporated within the ‘academic fantasy.’ What is important is not the philosophy itself – the description of philosophy as “affirm[ing] my belief that nothing is real and life is meaningless” while reading Crime and Punishment is quite an elementary view of the discipline – but being a person that “does philosophy.” Philosophy and reading are social rituals, activities that can be signified to the anonymous totality. The producer, in this case, is equally a consumer of their self-affirming practice. The distant incoherence of the social media “audience” means that this signifying process is unique to digitalized subjectivity. One may, for example, wear a nice shirt or act differently to impress a crush, but this process always has a specific target. On TikTok, there is no clear target (even when the video has ‘someone in mind’), just external distance. The algorithm sorts the audience for you; Inversely, it equally filters readily watchable content for the consumer. Within the digital communicative space, there is no meaningful, stable ‘consumer’ or ‘producer’ attribution, irrespective of the advertisements and data being collected. The total abstraction of the signifier detaches meaning from the subject, where language is repurposed, decontextualized, and recycled.

This recursive abstraction of meaning is a structural transformation in how democracy functions. There is no “political sphere,” because politics are a terrain of fantasy and digital consumption. Highly shareable infographics are a castrated politics, sublimated within the logic of digital exchange. They presuppose an individuation of democratic agency, whereby “enough shares” or “enough awareness” is sufficient for genuine political engagement. Democracy appears active while its capacity for collective action erodes: “Trump’s killing democracy? That seems bad. I know I am powerless, but at least I shared some mundane ‘gotcha’ on my story!” The alternative is posting ideologically informed, trivially mundane outrage.

The digital subject compulsively engages, not to change political reality, but to sustain the conditions of their own participation. The subject enjoys the contradiction of their digital political existence, transfixed by democracy’s simulation, even as democracy itself dissolves.

[1] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism.